Do poop transplants work for IBS?

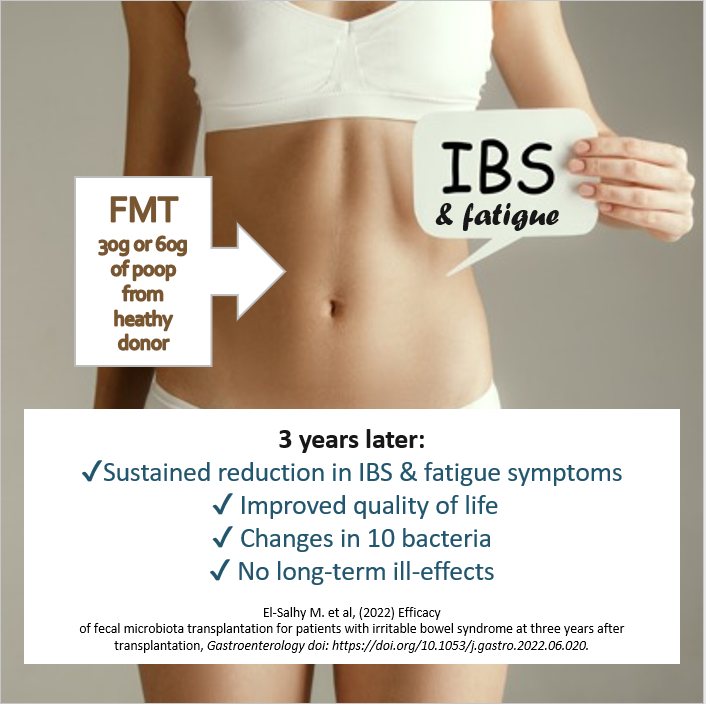

Have you ever considered a microbiome transplant to treat your IBS? A new study has revealed more about the long-term effects.

Irritable bowel syndrome can have a massive impact on the quality of life of sufferers. The gut symptoms and fatigue can be hard to live with driving sufferers to try a wide range of diets and medications. Others are tempted to try a poop transplant to swap in a new gut microbiome with the hope of improving their symptoms.

This month we report on a brand new study that reveals more about the long-term effects of this approach.

The Microbiome

Over the last few decades, knowledge has grown about the important role played by the microbiome in maintaining your health (see our blog Everything you need to know about your gut microbiome and why you should care).

Whilst we know that a diverse microbiome with a great variety of microbial species is generally good for you and that some families of bacteria and more beneficial than others, the specifics about what constitutes a healthy microbiome are still difficult to define. One obvious broad brush-strokes approach that bypasses this problem is transplanting a whole gut microbiome from a healthy individual into someone with gut problems. The hope is that the good gut health will transfer with the poop.

What do we mean by a transplant?

Whilst a pill containing bacterial spores from human microbiome is in development, the transplant process is still quite unsophisticated at this point. It involves the transfer of minimally processed faecal matter (poop) from a healthy person to a patient with the aim of repopulating with a new healthy microbiome leading to recovery.

The process is called Faecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT). And whilst the yuck factor may be strong, it has the advantage of transferring a whole balanced ecosystem of bacteria that may work together in a myriad of ways to provide health benefits to the new human host.

This process is relatively new to Western Medicine, but it turns out that FMT was described 1,700 years ago by an ancient Chinese researcher by the name of Ge Hong, who used what he called ‘yellow soup’ to treat his patients with severe diarrhea.

In recent years, FMT researchers have used FMT with varying success to treat the deadly gut infection Clostridium difficile, inflammatory bowel disease and metabolic diseases.

How about FMT for treatment of IBS?

A new paper reports the results of study investigating how effective FMT is for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

The study came out of Norway and was led by Prof Magdy El-Salhy at Stord Helse-Fonna Hospital.

What was exciting about this study was that it involved a broad range of participants with different types of IBS, different ages and both males and females. It was also a long-term study.

Who, what, when?

IBS patients were randomly allocated to one of three different groups: a control group receiving a sample of their own poop, those receiving 30g of poop from a healthy donor and those receiving a larger 60g dose of poop from the healthy donor. They were then followed up at 2 and 3 years and surveyed about their IBS symptoms, fatigue levels, their quality of life and poop samples were taken to assess the diversity of their microbiomes.

The length of the study was important because previous studies have been short-term and many doctors have questioned whether any positive effects from FMT are maintained once a patient returns to their usual diet and environment, or whether the microbiome reverts to its old state and the symptoms return.

What did they find?

The results were good. The one most of us care about is the change in gut symptoms. This was assessed using surveys including the IBS Symptom Severity Scale or IBS-SSS. Higher points on this scale indicate more severe symptoms. All three groups started with similar average symptom severity (around 315). The IBS-SSS remained at this level in members of the control group that received their own poop, but decreased in the groups that received a transplant from the healthy donor. At 2 years after the transplant it had decreased to an average of 179 in the group that received the 30g sample and down to 156 in the group receiving the large sample.

After 2 years, 30% of the 60g group had dropped below the level (75 points) that indicates complete remission. This percentage had decreased a little by 3 years but was still significantly different from the controls. Response rates were better in the women than men, but IBS type made no difference.

They also calculated the rate of ‘responders’, defined as those dropping more than 50 points on the IBS-SSS scale. The rate of responders was 72% of the group that received 60g of donor’s poop compared to 65% of the 30g group and 27% of the control group.

Fatigue and quality of life improved too

The team also found that fatigue levels benefitted from the FMT. The groups that received the donor’s poop had significantly less fatigue at 2 and 3 years than those that received samples or their own poop.

The survey on quality of life showed similar results. Quality of life scores improved the most in the group receiving the 60g dose from the healthy donor.

What happened to the gut microbiome?

In a bid to understand why the symptoms and quality of life improved, the researchers also looked at the microbiome, through DNA analysis of poop samples. The method used allowed the team to identify over 300 species of bacteria and to check whether their microbiome showed normbiosis (1 or 2 on the dysbiosis index) or dysbiosis (3 to 5 on the dysbiosis index). Normbiosis describes the state when the relative numbers of different microbes are typical for a healthy gut. Dysbiosis occurs when there is an imbalance and normally common species are rare and others increase to fill the gap. The researchers found that dysbiosis was removed as a result of the FMT. Dysbiosis decreased at both 2 and 3 years in the groups receiving FMT. They also found that the level of dysbiosis correlated with the severity of symptoms.

The researchers were able to uncover 10 changes in the numbers of particular bacteria or bacteria groups that appeared to underpin the response. We’ve popped these in the image below.

This work could help shape development of new probiotic combinations for treatment of IBS.

Key changes in the microbiome after FMT associated with IBS and fatigue symptoms

Any problems?

Where there any problems assiciated with the FMT? Previous FMT studies have thrown up some worrying side effects. However, in this study the negative events were largely limited to short lived nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, constipation, and one case of diverticulitis in the two days after the poop transfer.

The key take-aways

The specific FMT procedure used here was associated with sustained

✔ reduced IBS symptoms,

✔ reduced fatigue

✔ improved quality of life

✔ and was associated with only short-lived unwanted effects.

Things to consider

This is all very positive. However, it is worth pointing out that you may not wish to book in for your round of FMT just yet. There have been several other studies with mixed results. In four studies, FMT reduced symptoms and improved the quality of life of IBS patients, while no effects were indicated in the other three.

Why the differences? The study authors claim it is not by chance, but more likely due to different protocols for choosing a donor and preparing the poop. The Norwegian researchers were very careful in their selection of their donor, going all the way back to his birth to determine if he was likely to have healthy microbiome. He had been born by vaginal delivery, had been breastfed as a baby, and had only been exposed to a few courses of antibiotics. He also exercised regularly and ate a diet rich in protein, fibre, vitamins and minerals to support his exercise regime. The team analysed his microbiome and found it to have a high microbial diversity level that was consistent over time. Other researchers have not been so rigorous.

The Norwegian team were also careful to freeze the poop immediately on collection and to thaw only to 4oC and for a short time and to handle it very gently. These are all measures that have been demonstrated to maintain the microbial diversity within samples.

The research team also suggest that the site of application of the donor sample was important. They used a gastroscope to apply it to the duodenum, the part of the small intestine just after the stomach, rather than the large intestine.

If you do decide that FMT might be an option for you now or in the future, you may wish to ask your doctor about their specific processes and what their success rate has been over the longer term for patients.

Other IBS treatments

Alternatively, you may wish to wait for the FMT pill or a new super probiotic combo.

In the meantime, there are a range of management options you can discuss with your doctor, including the highly effective low-FODMAP diet. Our Superflora shakes make a convenient grab ‘n go low FODMAP meal option.

Warning

One thing we strongly recommend is not trying any kind of DIY FMT at home. Poop can contain harmful bacteria, and whilst a potential donor may seem healthy, they could be carrying disease causing organisms that make your health much worse.

Written by: Dr Mary Webberley, Chief Scientific Officer at Noisy Guts. Mary has a background in biology, with two degrees from the University of Cambridge and post-doctoral research experience. She spent several years undertaking research into the diagnosis of IBS and IBD. She was the winner of the 2018 CSIRO Breakout Female Scientist Award.