Everything you need to know about your gut microbiome, including why you should care

Did you know that there are trillions of bacteria, viruses and fungi in and on your body? You are literally walking around inside your own personal microbial cloud.

Like it or loathe it, more than half your body is bugs.

On our skin, up our nose, in every nook and cranny, our bodies are covered in bacteria. But what do we really know about the microbes living inside us?

With all the buzz around the gut microbiome, it can be challenging to distinguish between scientific facts and marketing hype. In this blog, we’ve pulled together the latest scientific research to help you understand how to eat your way to better gut health.

So what actually is the gut microbiome?

Our gut microbiome refers to the ecosystem of micro-organisms that live in our digestive system. Depending on who’s doing the counting, there are over 37 trillion and 5,000 species of microbes weighing approximately 2 kilograms, living mainly in our lower intestines. The ecosystem is made up of bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea and eukaryotes, collectively known as our gut microbiome.

We’ve come to think about bacteria, viruses and fungi as being “bad”. But the reality is that we NEED microbes to survive. In fact, the more we learn about what is living in our guts and what they do, the more influential we believe our gut microbiome is to good health.

Hmm, don’t we know someone that won a Nobel Prize for discovering bacteria in the gut?

Our medical advisor Professor Barry Marshall and his colleague Professor Robin Warren won the 2005 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Prof Marshall famously drank a petri dish containing the bacteria to prove the link between the micro-organism and stomach ulcers.

When the duo tried to get their work first published in 1983, their paper was rejected. Imagine a world where people believed that bacteria couldn’t live in our guts!

What’s the difference between prebiotics and probiotics?

Ever wondered why your GP recommends probiotics after taking antibiotics? Antibiotics kill or slow the growth of ‘bad’ bacteria. But they also destroy ‘good’ bacteria in the process.

Probiotics are the ‘good’ or beneficial bacteria that protect you from harmful bacteria and fungi. But before you race to the shops to buy some, introducing live bacteria into an ecosystem is only beneficial if there’s ample food supply. And what do probiotics eat? Prebiotics! Prebiotics are a vital food source for bacteria.

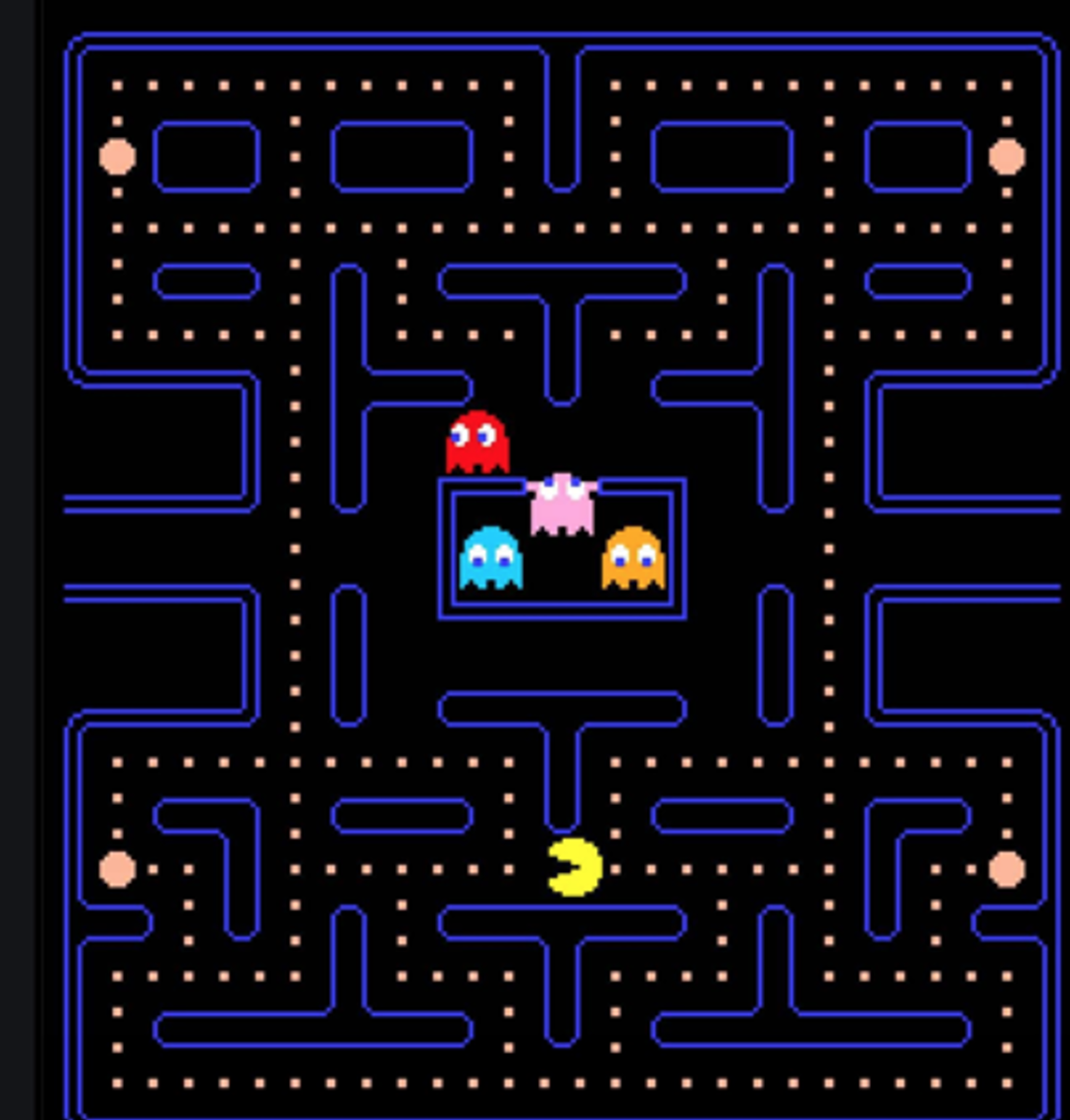

Think of your gut like the action maze video game Pac Man. The Pac Man (probiotics) eat all of the dots (prebiotics) in the maze while avoiding the ‘baddies’ (antibiotics, environmental stresses, processed foods, etc.)

Why does my microbiome matter?

Research into the gut microbiome is exploding. The field of metagenomics (the study of micro-organisms) catapulted in 2005 when next generation sequencing technology enabled the study of microbiota living in our digestive tracts.

But the field is still in its infancy. Scientists are still working out what lives in our gut, what role each species plays, and how our microbiome affects our physical and mental health.

The balance between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ micro-organisms in our gut is implicated in better weight management, heart health and mental health. When the microbiome becomes imbalanced by environmental factors, stress, antibiotics or poor diet, the gut barrier is compromised. This means that bacteria can “leak” into the bloodstream triggering your immune system.

While few associations have actually been demonstrated in humans, scientists believe that a healthy gut microbiome probably has wide-ranging implications for diabetes, obesity, irritable bowel syndrome, allergies, autism, depression, Parkinson’s disease and more.

Scientists have recently established that the gut microbiome differs between healthy people and diseased people. Specifically, studies of people with diabetes (Halawa et al, 2019), obesity (Shen et al, 2019) and irritable bowel syndrome (Menees and Chey, 2018) confirm that if you suffer from one of these conditions, you have less diverse microbiomes than your healthy counterparts.

Is my microbiome unique to me?

Yes, fancy that! You really are one of a kind. Your gut microbiome is more unique than your fingerprint. But herein lies the problem. It’s difficult for scientists to determine a “normal” or “healthy” pattern of microbes because every body’s microbiome is different – even in identical twins! This makes working out what a healthy microbiome looks like really difficult.

Does my microbiome change as I get older?

Scientists now think that your gut microbiome develops in the womb and is affected by delivery type (vaginal or cesearean) and early feeding (breast or bottle). Our gut microbiome continues to develop until 2-3 years, after which it remains relatively stable throughout adulthood.

As you get older, your microbial diversity decreases and this reduction in diversity is correlated with nutritional status, increased inflammation and frailty.

Hot off the press research now shows that long-living people (including those that live to 100 years) exhibit increased gut microbial diversity (Leite, et al 2021). If you want to live to a ripe old age, then you must nourish your gut bugs.

What can I do to improve my gut microbiome?

Yes, we can eat our way to good gut health. But we’ve got to expand our food horizon.

Diet is the most powerful influence on our microbiome.

Professor Tim Spector is leading the UK/British citizen science Gut Project. The project is an open source crowd funded project that relies on volunteers sending their poop samples in the post. The key finding is that microbial diversity is key.

Eating a wide-range of plant-based foods such as seeds, herbs, spices, nuts, legumes, fruits and veggies – all provide fuel for our microbes.

Conversely, sugar, antibiotics and processed foods decrease the number and diversity of our microbiota.

So what can you do to improve your gut microbiome? Aim to eat 20+ plant-based foods per week and avoid antibiotics, where possible.

Here’s what Australia’s favourite doctor Norman Swan says about antibiotics in his latest book “So you think you know what’s good for you”:

“Antibiotics are important if you need them but… There is evidence from both animal and human studies that antibiotic use increases the risk of cancers in general and bowel cancer in particular”.

Why is fibre so important to gut health?

Fibre is food for your gut bugs.

Professor Spector volunteered his son Tom to undertake the McDonald’s 10-day challenge. Tom survived eating McDonalds for 10 days but I bet he dined out on the findings for years. There was a 40% decrease in his gut diversity and he lost 1,200 types of bacteria.

But it wasn’t just about the high level of fat and sugar in the junk food he was eating. The lack of fibre in his diet meant that there was simply no food to feed the good bacteria in Tom’s digestive tract. And that just lead to bubble, bubble, boil and trouble.

Researchers have moved well beyond thinking about fibre as simply roughage to keep you regular.

When fibre ferments in your lower intestines it produces short-chain fatty acids called butyrate. These fatty acids are critical to the health of the bowel lining (stops leakages) and stimulate immune messages. Without these fatty acids, the bowel lining becomes compromised and inflamed.

And in even more good news, there’s good supporting evidence that eating a plant-rich diet with lots of soluble fibre (think oats, peas, beans, carrots, psyllium and citrus fruits) may prevent bowel cancer.

Will probiotics help my IBS?

There is mixed data in the medical literature about the benefits of probiotics for those that suffer from Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). This is probably because there are so many different probiotic options. However, many experts do recommend adding probiotics to your diet along with dietary changes, exercise and relaxation as a great first line management approach.

We chose to add a strain of probiotic with clinical evidence to our Superflora shakes. In a clinical trial of LactoSpore Bacillus coagulans MTCC 58566 effectiveness published in 2016, there was a significant decrease in symptoms like bloating, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain and stool frequency in the patient group receiving B. coagulans MTCC 5856 when compared to a placebo group.

Bacillus coagulans has been used in Japan to make natto and functional fermented foods. It is believed to retore microecological balance by out competing the bad bacteria and by producing lactic acid, hydrogen peroxide and bacteriocins which also keep the bad bacteria in check.

Our shakes also contain 7g of fibre, contributing to the prebiotics needed by the B. coagulans and other good bacteria.

What foods should I eat to improve my gut health?

Eat the rainbow. - Check out the meal plan in our Good Gut Challenge.for ideas.

The take-home message is that microbial diversity is key to good gut health and that means eating a wide variety of plant-based foods. Experts now suggest 20+ different plant-based foods per week.

Here are 5 easy ways of improving your microbiome:

1. mix 2 tablespoons of nuts and full-fat yoghurt to your fruit salad

2. add 1 tablespoon of mixed seeds to your cereal

3. incorporate more colour into your salads with a wide mix of veggies

4. ditch white rice and replace with red, black, green or brown rice varieties

5. fall in love with chia seeds

You’ve come this far - want to read more?

Want to read more? Here are some research articles (and the video of Tom Spector eating McDonald’s) that will provide even more fuel for your brain:

· 2014 oldie but a goodie research paper on the gut microbiome

· How does food affect your microbiome (and what happens to your microbial diversity if you eat McDonald’s for 10 days)

Check out our other Blog posts for more gut health information.